Expedition Cluster Ballooning:

Trans-Atlantic Attempt:

~The Newfoundland Express~

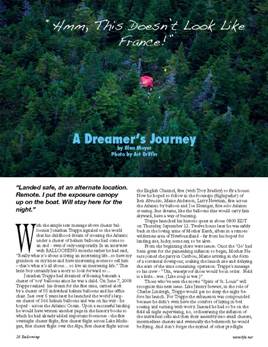

I mounted an expedition to cross the great Atlantic Ocean. It became the greatest flight of its type, a great success, and a spectacular failure. I wrote the below account in Newfoundland immediately after landing, while still on the island, during the recovery of the aircraft from the remote landing site.

Tremendous, Beautiful, Magnificent Failure!

So beautiful, what we have done.

What a night in foggy Caribou, what a team on the airfield, what adventure, writ large. What friendship, camaraderie, and love. What a gorgeous failure. What a flight!

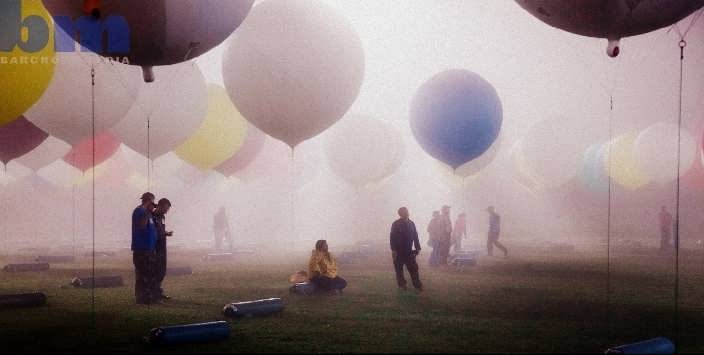

Nobody has ever flown this type of system further than we did, and nobody has ever failed with a system like this as well as I did in the sky these past days. Nobody has built a cluster of balloons this large; nobody has ever launched a cluster of balloons into manned flight so beautifully. The balloons, the colors, the lights of the Soucie Memorial Airfield shining down through the mist. Were you there? Do you remember? Will you remember it forever?

I will.

Inflation & Launch:

Perfect. Uncommon. Spectacular. All of these things for the people of the County, the people of Maine, the balloonists and team that came together on the airfield and assembled this aircraft. Wasn’t it perfect?

I went into the night with tremendous, non-trivial fear. Years. I had worked towards this for years, and put all of my energy, focus, money, and love into this flight. Then, a storm came in, so fierce, so terrible. I sent out a confident email, saying we would be ready, and everybody should go to the airfield. Then the sky dropped, my stomach failed, and I broke down with the sky falling on all of us.

I went into the night with tremendous, non-trivial fear. Years. I had worked towards this for years, and put all of my energy, focus, money, and love into this flight. Then, a storm came in, so fierce, so terrible. I sent out a confident email, saying we would be ready, and everybody should go to the airfield. Then the sky dropped, my stomach failed, and I broke down with the sky falling on all of us.

The storm was so bad that it triggered tornado warnings. And, I’m supposed to inflate balloons a couple hours later—hundreds of them, building a system taller than a church steeple.

And then she cleared. The sky cleared. The people of Caribou came. As our great City Manager Austin Bleess said, the people of Caribou will not let you down. They did not let me down. We built the aircraft together in the mist, and floated her into the quiet sky.

Meteorologist:

Perfect and clear. Trajectories as he forecast. He read everything perfectly. I would have never had my dream without him. He delivered well. He delivered.

All was as the meteorologist said. He was there for the months leading into the flight, and for the intense days leading up to the GO decision. He was there up through the last briefing on the airfield, as the system was assembled and he gave my final briefing as I hung off the back of the gondola and spoke with him on the phone, as the media team watched on. He was there after launch. He was there for the entire flight. After landing, he stayed with me until I was safe again. A great man.

Launch:

A gorgeous calm on the Soucie field. A gorgeous moment. My loved ones there. My greatest ballooning friends there with me. A hero of this country, the legendary Col. Joe Kittinger, on the airfield, with his hand on his heart as our National Anthem played.

She wraps a scarf around my neck; I touch the hand of Col. Kittinger and ask that he release; he tells me I am living my dream.

The music, our country’s national anthem comes to a crescendo.

I let go of red one bag; I drop her to the ground. I let go of one red bag, I let go of this earth, and I depart.

Into the quiet sky:

Only perfection as we join the color in the sky. A slow, dreamy float out. Music below me. Children below me. They call up to me. They wish me well. I float away from everyone I love, and away from the city, the county, the country, the land, and everything I know.

The sky that looks so warm will soon be so cold.

Terror:

To fail, in such a magnificent way. Now that the data is in, we can see it so clearly. We created that data. Together, with what we built, we created that data. We did it; we sought out what we yearned for, in ways both concrete and ethereal. Now the data is in, and a 15-year old could read it. We found the answer for this type of system.

For me, up, so high—23,000 feet. Down, to the deck—though never in the water. Up, into the gorgeous, ragged skies.

I launched wet. The mist condensed on the balloons, and it rained down on me. I launched wet—soaked. I climbed into the sky. The temperature dropped. My wet hair froze. My clothes froze. The droplets off the balloons stopped. Then, they started to snow. My balloons created the first snowfall of the year over Caribou—in September. The first snow over Caribou in 2013 was delivered by balloons.

I striped off my clothes. Naked, freezing in the thin air, so cold. I was stripped. I am thinking of Ben Abruzzo in 1977, nearly frozen to death, with frostbite injuries that would cause him pain for the rest of his life. I had to get the wet clothes off. I retrieve gear, and I am into dry clothes; better for these thin and ragged skies.

Excellent communication with Boston Center on the aircraft radio. Beautiful radar contact. Smooth transition to Moncton center. International flight! Into Canada. The Photographer of the County, Mr. Paul Cyr, operating in his element, perfect as he has ever been, taking photos you have all seen, and I will treasure forever.

Out. I fly out over the great Gulf of St. Lawrence:

Out. I fly out over the great Gulf of St. Lawrence:

Failure. Cell failure. Freezing of the wet balloons. Ascending out above a cloud layer. Heating of balloons in the sun. Oxygen tubes in my nostrils, feeding me precious O2, to clear my head. Fatigue. Simple Human Fatigue. Aircraft not performing. My aircraft not performing. Not flying the way I need her to.

Using ballast. Burning ballast. Too fast. Too fast, I’m using my ballast. At this rate will I make it to….France? No. England? No. Ireland? no. no. no. All no. Too many no’s. All no’s, and too many. Too fast. The ballast use is too fast.

Live. Die. Fly. Land.

Land. Yes, that one: Land.

Newfoundland:

I’m making 50 knots. My god, so fast, in the sky. But, the sky is failing. The light is failing. The sun has set. And I am over water.

I have the coast of Newfoundland in front of me and fast approaching – but it has been that way for hours. 300 miles over the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and I race to land, but not before the sun drops.

Still grey. The sky is grey, and not yet black. But fading fast.

I am reaching the coast in that grey.

I cannot see where the water ends. I cannot see where the shore starts. All I see are the mountains. No—not mountains—only the tops of them, with their bases secreted far below, down under the cloud layer. All I can see are the tops of mountains, and where I would see blueberry fields, or potato fields, or arroyos, or soft hay fields, or grass, instead I see reality: THE NEWFOUNDLAND COAST, serious, sharp cliffs. I see no valley, because it is obscured. I see no grass, because that is only what I would want to see, not what really exists. Instead I see only those sharp, grey cliffs.

But the valley is there. The GPS feeds me. I know the valley is there. I make landfall. Landfall. Landfall. Over the mountain, in the grey, and cut balloons. VENT helium. Come down. I have made landfall. I am over the mountain. Watch the GPS. Don’t use my eyes on the ground—because there is no ground there. Only the grey, the clouds, the mist, the moisture that takes all my eyes can give, and in return give nothing at all. Use my eyes on the GPS, and observe altitude, rate of climb. No—rate of descent. Get it down. Get it down, before the sky goes black.

I can’t make it to Europe. But I can’t stay here. If I wait 15 more minutes, it will be dark, and I can’t land at night. If I stay up all night, at 50 knots, I will be out to sea before sunrise. Land now, goddamnyouJonathan.

Cut balloons. Descending so fast. Cut a bag of ballast in the mist….and listen. Listen. Listebooom! Bag hit. There must be ground down there. (It is not a conspiracy of cartographers.) Get down. I’m hooking; my track is hooking. Get down, before the black comes. Get dow--- TREES. I see them below me. Some distance yet; some hundreds of feet. Slow the descent! Cut bags.

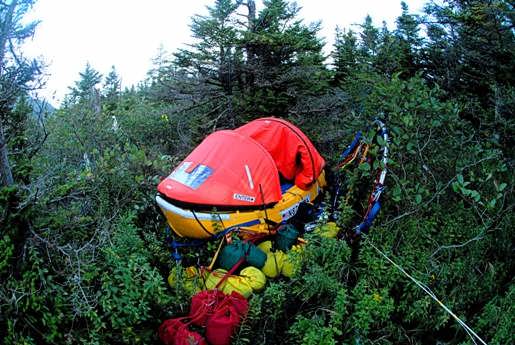

Prepare to cut more bags. No—no--- it is time for the trees. CUT THE BALLOONS. Don’t drag through the forest. CUT THE BALLOONS. And I do. I stab myself in the heart and let go of my balloons. Cutting lines, so fast. The scissors in the gondola at my feet are under something. Instead using the knife—no time to find the safety scissors, with their blunt point that can’t cut me. Using the knife, and I’m slashing, and slashing, and I’m down into--- treetops.

I’ve arranged the ballast so it hits first, and acts as shock absorber. It hits first, the camera arm shears off on a tree and I am…. I am……

Where am I? Down? Not moving. Up? On top of….something? But I’m down. I feel I am down. But down on what?

Down, in this land, where I write you from now. I write you from the home of a journalist and his wife. Moose stew. Halibut. Bake apples on ice cream. But, we’re not to that happy place yet.

Overnight:

I cut away all balloons, I kill myself, and I cut them all away-- and I’m down on something, and surrounded by trees. Rain is coming. The night is here. I use the sat phone and tell the team I am living. They will relay safe landing and ‘no-emergency’ status to the aviation authorities. We tell them there IS NO EMERGENCY. Kevin. Phil. Mark. Tom. Don. They are there for me. They are rocks.

Rain coming; I prepare. I bring up the exposure canopy. I put gear into plastic. In all my preparations, I never bought bug spray. (Lies: I bought 3 bottles of the strongest-- for the inflation team; those bottles are left in Caribou. I would pay $100 for one of them now.) So. Many. Mosquitoes. What is this place that I have landed in?

Rain coming; I prepare. I bring up the exposure canopy. I put gear into plastic. In all my preparations, I never bought bug spray. (Lies: I bought 3 bottles of the strongest-- for the inflation team; those bottles are left in Caribou. I would pay $100 for one of them now.) So. Many. Mosquitoes. What is this place that I have landed in?

I post a message via the sat messenger to Facebook, trying to let everybody know that I am down, and will stay put here tonight. It is true; this really doesn't look like France.

Rain in the night. I stay dry, in my shelter. I put up the exposure canopy. I put on the cold-weather suit. I sleep.

Dawn:

I am in a bog. That is the word the Newfoundlanders use. Bog. That is that…thing….that I am in, that didn’t feel like ground, but didn’t feel like trees.

For the first time in 24-hours, I step out from the gondola. After sleeping in my capsule, with my mosquito mates that I started naming before my consciousness failed. After sleeping, and after the sun has come to this land, I open the canopy. I survey the surroundings. Impassable. This is completely impassable. Completely. No ATV could make this. No tank could make this terrain. No boat. Nothing could get to this spot via ground transport. Impassable.

"A remote spot in Newfoundland." There must be a joke in there somewhere.

Sorting:

It is the dawn of the day after I flew, and I start to sort the site. My crew works with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police to tell them there is no emergency. But, they want to come out. Um, ok—but no SAR, no emergency. Do not initiate a rescue. I don’t need rescue. I am working on commercial recovery—where I hire a helicopter for retrieval. That’s OK, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police say. They just want to come say hello. Ok, I’m not opposed to company.

I have 60L water, 38L Gatorade, 65,000 calories food. I have shelter, sleeping bags, cold weather gear. I have my stove, and could make a coffee. But, instead I start sorting the site. So much gear to sort, in a small space. I hang things on the trees—empty ballast bags. I work to clear an area. I stop and use the sat phone and sat messengers—so many people to inform, with different info.

My dedicated team is working and communicating all on my behalf. They make sure that the Canadians know there is no emergency, but that I am there, safe, and working on commercial recovery. My team continues to operate beautifully, and dedicated. Even the meteorologist sends me new, updated weather info for the coming day.

Half a day of this. Sorting. Messaging. Talking.

I am on the sat phone with the RCMP commander when a helicopter appears overhead.

CBC: The CBC wanted an interview. I mean, they *really* wanted an interview:

The CBC had been out all morning on ATV’s. They could be there still on ATV’s; they would never get to my site. There was some sort of arms race among the media types. Some arms race to escalate, in order to get to me first.

The CBC had been out all morning on ATV’s. They could be there still on ATV’s; they would never get to my site. There was some sort of arms race among the media types. Some arms race to escalate, in order to get to me first.

The CBC goes nuclear and rents a helicopter. It comes to me, right overhead. I am on the phone when the helicopter appears, and I tell the Royal Canadian Mounted Police commander on the SAT phone that a helicopter is here, and he says….Well, it is for you.

I hang up, and get on the aircraft radio—the emergency frequency to hail, then quickly to another frequency.

“Are you ok?”

Yes, yes—I am fine. No risk to life, limb, or vision. There is no emergency. I am fine here. Um…how are you? They are fine too.

Can we talk? They want to talk to me. Um, ok. There is a LZ 300 meters away. Ok, I’ll meet you over there.

For the first time on the flight, I get wet.

For the first time on the flight, I get wet.

Wet. Muddy. I slog it through the bog. Sometimes I’m tempted to just leave the damn shoe in the hole this time. But, that mudhole also has my foot. So, I extract both, and take another step. I do this for…a long time. I come to some river. I cross. It washes off the bog mud. Then, back into dense bog, and the mud comes back on, then a hill, then a clearing, and I’m covered in mud—that special bog mud—

As I climb up from that, this young CBC reporter is having the story of her young life. Her eyes are wide, and she is excited. Wait, I just flew from Maine to Newfoundland under a cluster of helium balloons, landed in a bog, slept there in the boat, named my mosquito bunkmates, and then slogged through it to come talk to her in her helicopter. Shouldn’t my eyes be wide, and hers calm and rational?

She is sweet, and I give her what she came for—words. The first words from the balloonist. She has a ‘get,’ they call it. She got the story. She beat the other media guys, who were still out there on ATVs. They may be out there still.

I give her words. 4 minutes of them. (They will later turn this into dozens of media hits on the nightly news, including many, many ‘live’ shots where the lovely young reporter is standing in a parking lot…. ‘live’ for no apparent reason except to introduce the clip and play a different slice of the same 4-minutes.)

Track:

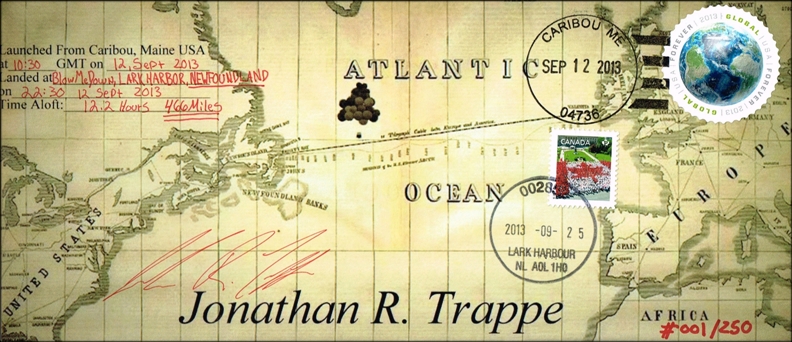

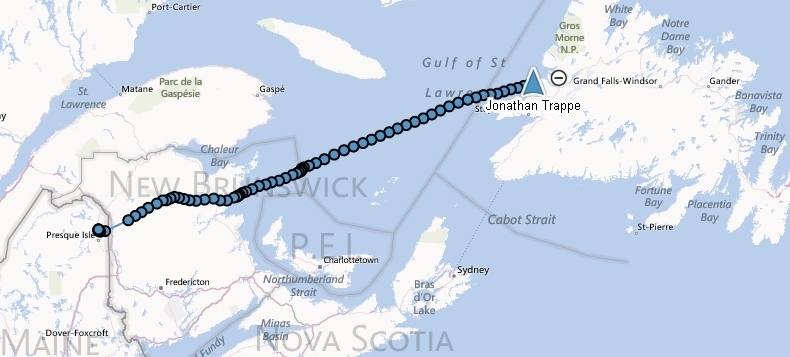

I had traveled 466 miles. In the history of manned flight, no one has flown an aircraft of this type that far. I departed from Maine USA, flew over New Brunswick, flew past Prince Edward Island, and I crossed out and over the great Gulf of St. Lawrence, a 318 mile open water crossing. Nobody has flown a system like this-- a towering cluster of helium filled balloons, carrying a man, this far.

I had traveled 466 miles. In the history of manned flight, no one has flown an aircraft of this type that far. I departed from Maine USA, flew over New Brunswick, flew past Prince Edward Island, and I crossed out and over the great Gulf of St. Lawrence, a 318 mile open water crossing. Nobody has flown a system like this-- a towering cluster of helium filled balloons, carrying a man, this far.

Tremendous success, in this failure. Tremendous success, in our attempt at even greater distances, greater accomplishments. I came to sharp cliffs at Newfoundland, rising over 1,000 feet out from the water. I came here. I would find out later that my landing site was perhaps fated; I came down alongside 'Blow Me Down Mountain.'

Ah, the great stories that it all makes.

Wind

The CBC offers me a ride. I had been securing the site, and I was going to hire a helicopter to come get me. But, here was this young CBC reporter, and a perfectly serviceable helicopter. Ok, I’m in.

Let me grab my passport, laptop (company issued laptop, thankyouverymuch), money, credit cards, wallet, film, cameras. Let me get my GoBag, with all of that.

The pilot screws up his face. (Can I write that in an email?) He did that. He made a bad face, and talked about wind. If I go back to the gondola and get my….life…that I have left there, the wind will pick up, and we will all be blown off the land.

I have to choose—right then: go on the CBC helicopter, with nothing on me but bog and wet shoes and bog, or let the helicopter fly away and I go back to my site. Wet. (I wasn’t wet until the CBC came!)

Ok, let’s go.

We go

To a forestry station, where I am greeted by three men and one bear. I think the bear was unrelated. I don’t mean it wasn’t related by blood to the men. I mean, I think the bear was there—big and angry— for a reason unrelated to ballooning, or my coming. I think the bear was there because it was a forestry helipad, and they were doing something with the bear. I don’t know. I never got the story. As soon as I walked by the bear, he hit the cage with a giant paw, which was a trailer cage thing used to….transport bears, I suppose. Anyway, as soon as I walked by the bear, I was into the arms of the customs and immigration guys. (Metaphorically. Not literally. That would be weird.)

Do I have any goods to declare? Um, I have some…food and stuff. And a boat. Have I brought anything into Canada? Have I been on a farm? (Do bogs count? They grow mosquitoes quite well.) What do you mean, you have no ID. Nothing? Are you….employed? You look kinda ….messy.

YEAH. I AM EMPLOYED. YEAH, I LOOK MESSY. I JUST HIKED THROUGH A BOG TO GET TO THE CBC HELICOPTER.

One hour ago, I had 60L water, 38L Gatorade, shelter, food, clothing, and dry feet. Now I am like a refugee. A refugee that smells like bog, and has a *Highly Improbable Story* of how he came to Canada. I relay my Highly Improbable Story to the three men, but not the bear—because the bear was upstairs. We do the interview in the basement of the forestry building. Make a wrong turn in that building: bears. NOT KIDDING.

All the media reports said the area I landed in had bears. You know when I saw a bear? WHEN I GOT OFF THE CBC HELICOPTER.

My situation degraded dramatically upon encountering that CBC helicopter. I now have wet feet, no food (it is at the landing site), no ID, no money, no phone (all at the landing site), no nothing. I do have shoes (wet), pants (wet), shirt (wet)—look, from here on out, just apply the word Wet to anything I have. It will save time.

The CBC would later run the story: “CBC Rescues Balloonist.”

Wait. What?

To their credit, they would later update the headline to "CBC Helps Find Balloonist."

So, there I am—provisionally cleared to enter Canada. They didn’t deport me (though, that would have saved me an airline ticket.) I have nothing but wet mud, and a bear. The only bear I saw was after the CBC helicopter (did I mention that?) Word to the wise: if a man in a car offers you candy, or a pretty girl in a CBC helicopter offers you a ride, don’t take it.

Newfoundlanders:

Newfoundlanders:

Now is the time for this part of the story: Moose stew. Halibut. Bake apples—bake apples on ice cream. These things, and clean dry clothes, given to a man that has nothing and smells faintly of bog. (Not that faintly, actually.)

The hospitality of Newfoundlanders is legendary. They deliver. Art and Carol. They sheltered me when I had nothing at all.

One Day of Rain:

Saturday. The tropical storm Gabrielle caught up to me. We knew very well that the storm would be behind me during the flight, and if I stopped, it would catch up with me. But, if you are really going to cross the Atlantic, you aren't going to do it on a sunny day with no wind. We needed those same winds to move me across the water. We selected that day to launch specifically because of the wind conditions aloft. I had great winds, and great speeds-- touching 70 MPH aloft. That is perfect. If I kept flying, I would have been 30 hours from this site before the tropical storm came ashore-- easily more than 1,000 miles distant from where the storm came ashore in Newfoundland. That was well known. Since I stopped moving, the storm caught up with me a day after landing; this was known in advance and not an issue; it would mean that I had to wait a day for it to blow past before getting back to the site for retrieval.

One Day back out to the site, lifting the gondola out with a helicopter:

Sunday. Fast, furious recovery from the bog; by the time the helicopter can get out to the site, we will be dealing with failing light. We had to expedite everything; we had to pack and lift out the gear as quickly as possible, so as to not create a safety situation for the helicopter operator and ourselves. Everything I pack is packed rapidly, furiously.

|

|

|

|---|---|---|

Helicopter long line |

Preparing the lifting harness |

Preparing for lift out |

|

|---|

| Airborne again. This boat does fly more than most of its type. |

One day to say goodbye, and depart for NYC:

Monday. When I fly away from the island of Newfoundland, on the commercial jet, I think of the view I had just a few days before.

Team:

We built something amazing. We will remember this day. We set out for adventure. We found great friends.

Perfect:

So perfect, this great failure that was achieved on this flight. I land a much richer man than I launched. I leave Canada even richer still. I return to Caribou for my friends.

|

|---|

| Between Cloud Layers, over the Gulf of St. Lawrence |

For the great trans-Atlantic attempt, With Great Appreciation:

My heartfelt thanks go to:

- Our outstanding crew for their excellence on the airfield; I would never have had this opportunity without you; it is this team-- YOU-- that enabled this expedition-- a flight like no other.

- The City Council and the City of Caribou Maine, and the outstanding community leadership and outreach of Austin Bleess, Kathy Mazzuchelli, Gary Marquis, Dave Oullette, and Chief Susi.

- Col. Joe Kittinger, an aviation legend, for camaraderie uncommon.

- Don Day, Meteorologist, for helping us to read the skies, ride the winds, and arrive safely.

- The professionals manning the command center for their long-term dedication to the project, for their fluid communications with the civil aviation and SAR representatives during the flight, for watching over me in the sky, and protecting me at recovery: Mark Caviezel, Phil Bryant, Tom Mackie, and Kevin Knapp.

- Jim Rogers, for the exceptional assistance throughout the project, and for the days spent recovering the aircraft-- including two overnight ferries and the longest chase of his entire ballooning career-- which includes some notable gas balloon recoveries!

- The balloon builders that were with me for the months of preparation before the flight, for their workmanship on the aircraft components, and the advice and assistance in working with the FAA.

- The local balloonists of Aroostook for their welcome to the County, and for the opportunity to fly with you: Derik Smith, Milt Smith, Bud Hebrlee, Bill Belk, Dena Winslow.

- The amateur radio community for their extended dialog on HF radios, APRS, trackers, sat trackers, and for both building and loaning valuable gear to this uncommon project: Karl Gross, Bill Brown, Mark Caviezel, Tom Mackie, and Gary Snyder.

- For everyone that came great distances to be here at the launch, and were there with me throughout the flight and recovery: Mary Grady, Paul Stumpf, Noah Forden, David Hulbert, Jim Roybal.

- Art and Carol for their professional photography, for the trek back in to the landing site, for having me in their home, for moose stew, for bake apples, for halibut, for warmth, and for friendship in the welcoming province of Newfoundland.

- Rod Jandreau, Fran Piccirillo, and our industrial gas provider, for that precious, invisible, beautiful lighter-than-air gas and all the dedication it took to bring it to the field.

- Friends at the US FAA, Transport Canada, NavCanada, NATS UK, and the UK CAA for evaluating our unusual aircraft based on its merits, and for the tremendous professionalism shown throughout the process.

- Controllers at Boston Center, Moncton Center, and Gander Domestic for your professionalism, for watching over me in the sky, and for everything you did to make the flight safe for everyone.

- The great trans-Atlantic balloonists, for their advice as I followed my dreams: Don Cameron, David Hempleman-Adams, Dewey Reinhard, Christophe Houver, and Col. Joe Kittinger.

- Our Indiegogo team, for helping to create the flight! I will be sending you balloonmail that we carried on board!

- Alan Eustace for extended dialoging on lighter-than-air flight, for camaraderie, and for support of the expedition, including a piece of gear that may have saved my life.

- Born at Christmas for humor, intellectual inquiry, and for gracious coverage of our flight.

- Kevin and Kate McCartney for introductions to our local Rotary clubs, for having me in your home many times, and for unflagging support of our uncommon flight.

- David Barbosa, Raymond Burby, and the entire contingent of 33rd Composite Squadron of the CAP for support throughout the summer, and for helping stand the aircraft on the critical night.

- Dave Palmer, for outstanding graphics, and for helping us develop sponsorship for our unique sport.

- Paul Cyr, for his breathtaking photography.

- Joe Sleeper for gear that kept me safe in transit, and in recovery.

- Friends at Yellowbrick Tracking for use of the device that became the key connection to my team while in the air, and during the complex recovery; the device kept me in contact even in the most remote areas.

- Steve Hollinger and Kayalu for creative camera mounts that allowed me to share the story of the flight.

- Brad Stankey and Mountain High Aviation Oxygen Systems for use of professional oxygen systems that sustained life at critical altitudes during the extended flight.

- Sam Barcroft, Liam Miller, Laurentiu Garofeanu, Alex Ayer, and Jack McKay for flexibility, dedication, professionalism, rapid execution, and expertise in their specialties.

- Endless thank you to Nidia Ruiz Ramirez.

~FIN~

|

||

|---|---|---|

| The Times UK .pdf | ||

|

|

|

| Aerostat Magazine, UK .pdf | Ballooning Jounal, USA .pdf | Ballon Sport Magazine, Germany .pdf |