America's Challenge Gas Balloon Race! October 6th- 9th 2008: "Rainbow in the Dark"

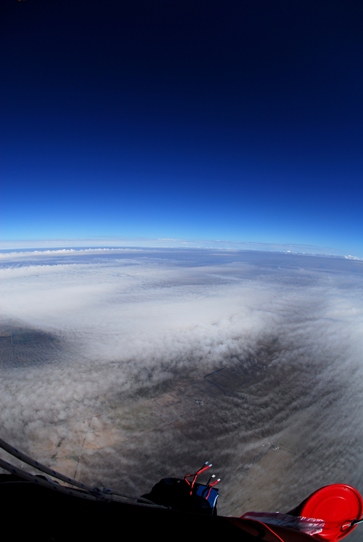

Aloft over Clouds during the 13th America's Challenge Gas Balloon Race

For several days in October, I lived in the sky.

For several days in October, I lived in the sky.

Above mountains, mesas, canyons and plains, I lived in the sky. For several days, a small wicker basket would carry two people, myself and pilot Troy Bradley, over six states. The sky during those days would also play host to 16 other gas balloons from around the world: France, Germany, Great Britain, Austria, Switzerland, and the United States. All of us had our own reasons for putting ourselves aloft for so many hours, but the overall goal was the same- distance. Six countries were represented in the sky, and we all wanted to travel the greatest distance from our launch site in the high New Mexico desert.

Two races would take place simultaneously: The 52nd Coupe Aéronautique Gordon Bennett and the 13th America's Challenge. This year both were hosted by the world's largest balloon event: the Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta. The balloons would launch sequentially, in an order determined by drawing lots. We would all launch from the same airfield in Albuquerque-- the 'Gasballon Startzplätz' as I heard the Germans call it-- and we would all fly for many, many hours without stopping. It was a sweeping adventure that crossed the continent. Here's how I experienced it.

Before Launch: Weather, Strategy, & Missiles

The official start of the race was slated for 6:30pm October 4th. However, the launch window would be open from October 4th through October 8th at 11:59pm. We would launch with the advice and consent of event meteorologists and the event director. The official launch and start of the race could be any time in the window. At our first briefing we discussed race rules (who to contact if you land in Canada; Mexico was off-limits; the missile range may be persuaded to give us a small window, etc) and we were introduced to the event meteorologists, officials, and the team that would staff the gas balloon command center 24-hours a day, from the time the first balloon launched, until the final balloon landed.

The official start of the race was slated for 6:30pm October 4th. However, the launch window would be open from October 4th through October 8th at 11:59pm. We would launch with the advice and consent of event meteorologists and the event director. The official launch and start of the race could be any time in the window. At our first briefing we discussed race rules (who to contact if you land in Canada; Mexico was off-limits; the missile range may be persuaded to give us a small window, etc) and we were introduced to the event meteorologists, officials, and the team that would staff the gas balloon command center 24-hours a day, from the time the first balloon launched, until the final balloon landed.

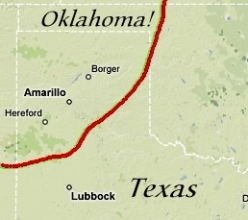

It so happens that at the opening of the launch window there was a wall of weather over 1,000 miles long, stretching from Canada to Mexico. If we launched Saturday night, we would fly right up to that curtain of weather and, if we were sane, land before progressing into the storms. The event director delayed the launch.

We met for our next pilot briefing on Monday, October 6th. The wall of storms had moved a little bit off to the east, but they could still be a factor. Fly too fast, and you could catch up to the storms and be forced to land. This makes for some interesting strategy: a team that flies too fast initially can catch up to the storms and have to put down the balloon. Then the patient balloons behind him can drag their feet, let the storms get further east, and overtake the balloons who were once in the front of the pack.

Through our own weather observations, it seemed Tuesday would make a good launch day for a long distance race. Launching Monday night would have us heading straight south, towards the active missile range at White Sands.

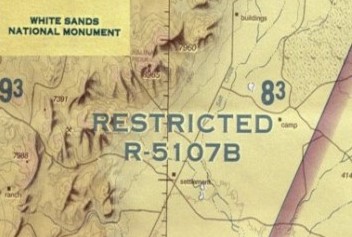

This is a very serious area: from the surface to 'unlimited' the airspace is Restricted. If you read the sectional for 'R-5107 B' it will tell you that the airspace is restricted 'continuously' and if you want to talk to someone on the aircraft radio to ask for permission-- well, tough luck. It simply says "No A/G." That is, no air-to-ground communication--there is nobody to even ask if you might cut across a little corner.

This is a very serious area: from the surface to 'unlimited' the airspace is Restricted. If you read the sectional for 'R-5107 B' it will tell you that the airspace is restricted 'continuously' and if you want to talk to someone on the aircraft radio to ask for permission-- well, tough luck. It simply says "No A/G." That is, no air-to-ground communication--there is nobody to even ask if you might cut across a little corner.

In fact, the entire south-central portion of the state is dominated by restricted zones for White Sands Missile Range-- it's the largest military installation in the United States. One would hope that an airspace incursion into this area would not result in being shot down. But, a missile range is a missile range. They once had an Athena missile go seriously astray: it launched from White Sands and went 400 miles down into Mexico. Best for our gas balloon to stay clear.

Also, with Mexico out of bounds for this race, we had yet another reason not to go south.

However, there was a bit of a surprise at our Monday briefing: we would indeed launch Monday night. Winds out of the north could push the balloons right towards the missile range, perhaps forcing a landing early in the flight. There was also another strategy element to consider: the winds would shift after the first 24-hours. If you rode the fastest winds at launch, you would go south towards Mexico, the missile range, and the restricted airspace-- and then when the winds shifted, the balloon that was furthest 'ahead' would be furthest behind!

Instead our strategy would be to 'drag our feet' the first day, trying to keep our distance to a minimum-- which is a bit of a strange thing to do, in a distance race!

Inflation: Standing the balloon, our "Rainbow in the Dark"

The event was go for launch. Tube trailers of explosive hydrogen and peaceful helium were on the airfield, waiting for the crews and balloons to begin inflation. Immediately after our briefing, a number of team members sprang into action. Garry Haruska would be our team's balloonmeister, responsible for standing up the balloon and preparing it for flight. We would be flying a Padelt built envelope over a wicker gondola. With good luck, we would be suspended aloft for days in that 3-foot by 5-foot basket. Garry was the man that would transform the aircraft from material stuffed in a stack into a proud piece of flying magic from aviation lore.

The event was go for launch. Tube trailers of explosive hydrogen and peaceful helium were on the airfield, waiting for the crews and balloons to begin inflation. Immediately after our briefing, a number of team members sprang into action. Garry Haruska would be our team's balloonmeister, responsible for standing up the balloon and preparing it for flight. We would be flying a Padelt built envelope over a wicker gondola. With good luck, we would be suspended aloft for days in that 3-foot by 5-foot basket. Garry was the man that would transform the aircraft from material stuffed in a stack into a proud piece of flying magic from aviation lore.

Fly One, a balloon team out of Saga Japan, helped to prepare the ballast bags we would use in flight. For those new to gas ballooning, this is how we stay aloft when the balloon cools at night and wants to descend: we release sand. It's also how we abort a landing; if we want to call off a site and fly on, we drop ballast. The Fly One crew and pilots filled most of our bags using the Fiesta field supply; we also had a several bags of 'dry' sand; if we were aloft in freezing temperatures for an extended period, the moisture in the field sand could cause the bags to freeze into bricks. Our dry sand would still pour, even very cold, so we wouldn't be up there chipping off blocks while trying to ballast.

We were off the field for much of the inflation. After launch

we would be aloft and awake for many hours, so we relied on our team to prepare the aircraft. Garry was the balloonmiester and he had things well in hand. As long as he doesn't have to chase the gas balloon, and as long as you're not asking him to fill a netted gas balloon [Down One Diamond!], he's your man.

We were off the field for much of the inflation. After launch

we would be aloft and awake for many hours, so we relied on our team to prepare the aircraft. Garry was the balloonmiester and he had things well in hand. As long as he doesn't have to chase the gas balloon, and as long as you're not asking him to fill a netted gas balloon [Down One Diamond!], he's your man.

When I again arrived at the field, it looked as pictured above: gas balloons from around the world were preparing for their endurance flights. I came to the aircraft, and inflation was already well underway. In fact, the balloon was already standing.

Repairs: Duct taping the balloon closed

I had been preparing for this flight for months. In order to fly in the event as a pilot, I had needed one more gas flight, with two final hours as pilot-in-command. This sounds simple: two hours. Except it can cost $10,000 to fill a gas balloon with helium in the United States. To prepare for this flight and get my pilot's certificate in order, we had to go to Germany and fly hydrogen to get that one flight in. With so much having gone in to preparing for this launch, there was a lot of emotion riding on getting this system aloft that day. We had an epic scale adventure in front of us. The realistic range of these gas balloons was the entire continent. Landing days later in Canada, Florida, North Dakota, Maine, or anywhere in between were all within possibility.

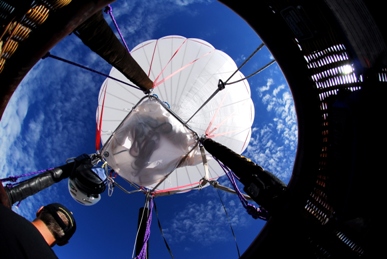

With that emotion riding high, we hit a problem. There are two ports on the bottom of the balloon: the appendix, and an emergency port. The appendix must remain open as you ascend in a gas balloon; it allows expanding gas to escape. If the appendix gets stuck closed, the gas will expand and put tremendous pressure on the balloon envelope, which can cause it to fail catastrophically. Thus the emergency port on the bottom of the balloon: if the appendix gets stuck shut, you can rip out the emergency port.

With that emotion riding high, we hit a problem. There are two ports on the bottom of the balloon: the appendix, and an emergency port. The appendix must remain open as you ascend in a gas balloon; it allows expanding gas to escape. If the appendix gets stuck closed, the gas will expand and put tremendous pressure on the balloon envelope, which can cause it to fail catastrophically. Thus the emergency port on the bottom of the balloon: if the appendix gets stuck shut, you can rip out the emergency port.

Except ours wouldn't stay closed.

The balloon was standing. The emergency port was well out of reach, and it was open. You could clearly see up into the balloon. My heart was sinking. So much to get to this point, and I was staring at a hole that I feared would keep us grounded.

There was no getting to that port without machinery. Luckily, Fiesta has machinery for just this purpose. They rallied up a cherry picker, and Troy Bradley went up to inspect. He brought along with him-- I'm not kidding-- a big roll of duct tape.

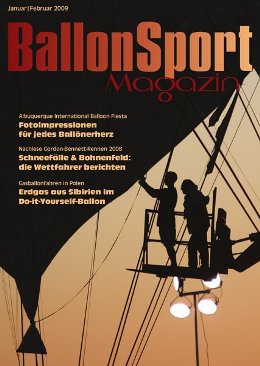

They tried to reassure me, insisting that we would only use that port in the event of an emergency. Um, however, that is a rather disconcerting thought. That is, if we have an emergency, and we really need it, then we'll be relying on the thing that we are now closing... with duct tape. [The German magazine 'BallonSport' seemed caught by the image, based on their January 2009 cover shot.]

They tried to reassure me, insisting that we would only use that port in the event of an emergency. Um, however, that is a rather disconcerting thought. That is, if we have an emergency, and we really need it, then we'll be relying on the thing that we are now closing... with duct tape. [The German magazine 'BallonSport' seemed caught by the image, based on their January 2009 cover shot.]

Well, the port was closed. The famed gas balloon race was in front of us. The sun began to set, the evening began and the field was alive with balloon teams, friends, spectators, pilots. Our balloon was standing, avionics were tested, emergency gear was on-board. In years prior, teams have flown for days and run out of food. I've heard the story, told from the event record holder, of cutting the last apple in half on the final day, and sharing it between the two pilots. As Bradley pointed out, we could always throw food overboard as ballast if we had to, but we couldn't eat sand. We had food for days.

It takes an amazing network to fly this race. There are twopilots in the air whose lives may depend on the people on the ground. Our balloonmeister must set up the balloon correctly; the gas balloon command center will track us closely while we fly and assist with airspace considerations and emergencies, if needed; our meteorologist Scott Risch in Omaha would be studying the weather systems in front of us and running trajectories, guiding us to fast winds and peaceful skies. Our chase crew of Nidia Ramirez and Joe Bosco would follow below us for the entire flight. Tami Bradley would serve as a contact and connection to the rest of the world. While in flight, we would use the satellite phone every two hours, alternating which group we spoke to. Family, friends, media, colleagues, and balloon aficionados around the world would track us throughout the entire flight.

It takes an amazing network to fly this race. There are twopilots in the air whose lives may depend on the people on the ground. Our balloonmeister must set up the balloon correctly; the gas balloon command center will track us closely while we fly and assist with airspace considerations and emergencies, if needed; our meteorologist Scott Risch in Omaha would be studying the weather systems in front of us and running trajectories, guiding us to fast winds and peaceful skies. Our chase crew of Nidia Ramirez and Joe Bosco would follow below us for the entire flight. Tami Bradley would serve as a contact and connection to the rest of the world. While in flight, we would use the satellite phone every two hours, alternating which group we spoke to. Family, friends, media, colleagues, and balloon aficionados around the world would track us throughout the entire flight.

Night came, and balloons began to launch. As each gas balloon was brought to the launch platform, their country's national anthem would play. Then, they would be released into the night.

Our turn was coming.

Preparing for Flight:

Our balloon was named Rainbow in the Dark. Troy Bradley and I were in the basket, surrounded by crew and loved ones. The gas balloon envelope was above our heads, much as it has been for the pilots that went before us in each of the 13 America's Challenge races, much as it had been for the pilots 102 years ago at the first Gordon Bennett. Balloons were already in the air, floating away into the night.

Our balloon was named Rainbow in the Dark. Troy Bradley and I were in the basket, surrounded by crew and loved ones. The gas balloon envelope was above our heads, much as it has been for the pilots that went before us in each of the 13 America's Challenge races, much as it had been for the pilots 102 years ago at the first Gordon Bennett. Balloons were already in the air, floating away into the night.

It was our turn. The event officials asked us if we would take our launch place, or forfeit our slot and be bumped to the end of the launch order.

We accepted our slot.

TheAmerican national anthem began to play as friends guided our balloon through the crowds towards the  launch platform. Garry Haruska, Keith Sproul, Nidia Ramirez, Tami Bradley, Joe Bosco-- friends and loved ones, took us tothe platform as we were announced over the field P.A. system. Up onto the platform we were turned over to

race officials who would perform the final weigh-off, ensuring that we would launch with sufficient lift to climb up and out.

launch platform. Garry Haruska, Keith Sproul, Nidia Ramirez, Tami Bradley, Joe Bosco-- friends and loved ones, took us tothe platform as we were announced over the field P.A. system. Up onto the platform we were turned over to

race officials who would perform the final weigh-off, ensuring that we would launch with sufficient lift to climb up and out.

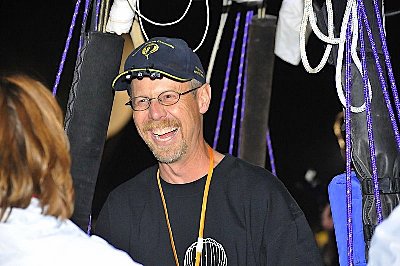

On the launch platform, the race officials checked our buoyancy: we were perfect. Troy laughed with the launch director Sabrina Handl as she confirmed we were weighed off correctly and would be clear to launch. The announcer talked about Troy's tremendous experience, such as having flown over oceans in a balloon. The announcer also joked that I've been known to fly an office chair (a true story, I might add.) Transponder was on; aircraft radio was on; I had our nighttime running lights in my hand so I could lower them below us when we lifted out from the field.

Music swells. Thumbs up from the launch master. Here it is. We're ready. WE LAUNCH.

Launch! Ascend, Into the Night:

We lift. Up, gently away from the platform. Cheering friends below us. I lower the lights below the basket, and I drop a parachute cow. That is, I had a little toy cow attached to a parachute, and I dropped it as we floated off the field; children raced after it to catch it as it floated down to them.

We lift. Up, gently away from the platform. Cheering friends below us. I lower the lights below the basket, and I drop a parachute cow. That is, I had a little toy cow attached to a parachute, and I dropped it as we floated off the field; children raced after it to catch it as it floated down to them.

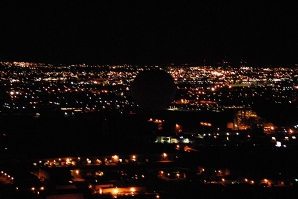

Wow, a year to get this gas pilot's license, and we were floating away from the launch site. Other gas balloons were flying very low against the city, hugging Albuquerque. Their shapes could best be seen by the absence of light. That is, the lights of the city blanketed the space below us-- except for certain spheres of black: the envelope of another gas balloon silhouetted against the city.

Wow, a year to get this gas pilot's license, and we were floating away from the launch site. Other gas balloons were flying very low against the city, hugging Albuquerque. Their shapes could best be seen by the absence of light. That is, the lights of the city blanketed the space below us-- except for certain spheres of black: the envelope of another gas balloon silhouetted against the city.

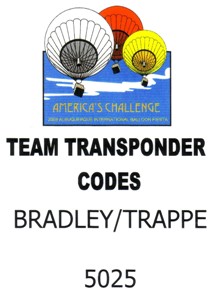

If you know Albuquerque, you'll know this landmark: we flew directly over the Marriott Pyramid. Low, slow we floated out over the city. The transponder was on, and we were squawking our assigned code: 5025. I was on the aircraft radio talking to Albuquerque International Airport. We were heading right for them. They were very well informed of our launch, and the night was full of the heavy accents of many nationalities talking to the tower: gas balloon pilots from around the world.

We were flying so low over the city that I could talk to people on the ground. "Where are you going?!" they called up to us. I confidently replied "Canada!... or Mexico!"

Perhaps that was a little ambitious for our first night.

Albuquerque International Airport, and Moons over Los Lunas:

We maintained close contact with controllers at ABQ as we approached their airport. With permission, we floated right by runway 26, just off the end of it. Balloons don't typically fly off of runways, especially at international airports. But, Albuquerque is special.

As we passed the airport, we were clicking along smoothly. Not fast, but more quickly than we wanted. As expected, we were going south-- and we needed to drag our feet. We identified other balloons floating in the night. Are we going faster than they are? Where is that slowest wind? We ballasted and climbed up into a slower stream of air. Near midnight we were over the New Mexico community of Los Lunas.

Stories in myth and folklore abound about coyotes and the moon. What a confusing night it must have been for them: the coyotes had a dozen moons floating over them-- our white balloons in the night sky. They paid appropriate tribute and serenaded us in the night.

Dawn over the Desert:

It had been a cold night. Even hugging the surface, we're up at altitudes several thousand feet above sea level. It's like camping in the foothills of the Rockies.In October. We took turns manning the ship: I slept for a couple of hours; Troy slept for a little bit. At 3:00 AM, in the darkness, we crossed the Rio Grande.

And dawn came; what had been a beautiful sight at night turned into a stunning spectacle of high-mountain desert. We had traveled about 30 miles in the night. Great: we were dragging our feet as planned.

Into daylight: The vast desert sweeps underneath us

Today will be an observation of great spaces: tremendous mesas, canyons, cliffs, riverbeds that must have once known water; we see other-worldly spires rise in the New Mexico Desert.

Today will be an observation of great spaces: tremendous mesas, canyons, cliffs, riverbeds that must have once known water; we see other-worldly spires rise in the New Mexico Desert.

We're headed west, away from the Sandia Mountains and into a beautiful space that isn't frequently flown in this race. First we come to Black Mesa, and we sweep south of Wind Mesa. We approach, ascend, and cross over Mesa Gigante as we turn to the North.

Troy was exceptionally good at spotting other gas balloons, far out into the horizon. We no longer heard them on the aircraft radio, and often they were just the smallest dots. There was a pair of balloons on the horizon that seemed to be locked in a duel. They were far to the north of us, and they were each clearly fighting something. They would be down to the surface, then slip back up -- searching the skies for something.

Troy was exceptionally good at spotting other gas balloons, far out into the horizon. We no longer heard them on the aircraft radio, and often they were just the smallest dots. There was a pair of balloons on the horizon that seemed to be locked in a duel. They were far to the north of us, and they were each clearly fighting something. They would be down to the surface, then slip back up -- searching the skies for something.

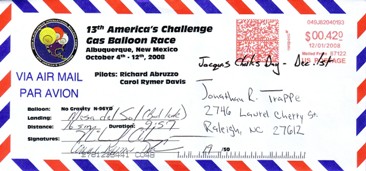

Mid-morning, we heard competition news from our crew. Over the satellite phone came the message: one balloon has landed. After about 10 hours in flight, the balloon 'No Gravity' had come back to earth. This balloon was piloted by world-class balloonists Carol Rymer-Davis and Richard Abruzzo.

This accomplished team has won both the Gordon Bennett and this race, the America's Challenge; Richard flew the Atlantic Ocean with Troy in '92. The note written on their balloon mail tells some of the story: 9 hours, 57 minutes in flight, landing at Mesa del Sol (Bad Luck.) An unfortunate problem had struck their system: a hole in the balloon. They had used half their ballast, intended to last for days, to stay aloft and safe for the first night. With the quantity of ballast they had remaining, they made the decision to come back to earth and fly another day.

This accomplished team has won both the Gordon Bennett and this race, the America's Challenge; Richard flew the Atlantic Ocean with Troy in '92. The note written on their balloon mail tells some of the story: 9 hours, 57 minutes in flight, landing at Mesa del Sol (Bad Luck.) An unfortunate problem had struck their system: a hole in the balloon. They had used half their ballast, intended to last for days, to stay aloft and safe for the first night. With the quantity of ballast they had remaining, they made the decision to come back to earth and fly another day.

It was around this time we came to a home perched up on a cliffside. It was the first structure of any sort we had seen for some time-- it was a pretty remote area. Then, there-- well below us-- a home was perched on the top of a mesa, built right up to the cliff's edge. If you click on the photo, or any of the photos on this page, you'll get a larger view. You can see the house drift below us, right in the center of the frame. You'll also get a feeling for how remote some of these areas felt.

It was around this time we came to a home perched up on a cliffside. It was the first structure of any sort we had seen for some time-- it was a pretty remote area. Then, there-- well below us-- a home was perched on the top of a mesa, built right up to the cliff's edge. If you click on the photo, or any of the photos on this page, you'll get a larger view. You can see the house drift below us, right in the center of the frame. You'll also get a feeling for how remote some of these areas felt.

So many moments like this during our America's Challenge flight-- splendor, vast spaces, interesting items, things that I want to come back and see. Such a unique way to explore the earth. Wonders abound on a gas flight.

The time of quiet struggle:

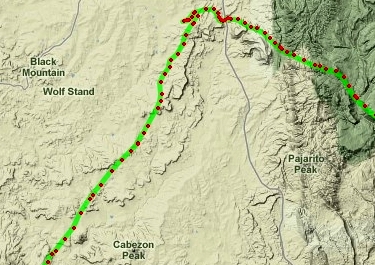

Our track was now steadily to the north-east. Staying slow through the night had its desired effect: we avoided the faster wind that would have sent us down to White Sands. Recall that earlier in the morning we had watched two balloons on the horizon working tremendously hard. Once we passed Cabezon Peak, the lands of carved trenches, canyons, and mesas transformed into a more open desert plain.

Our track was now steadily to the north-east. Staying slow through the night had its desired effect: we avoided the faster wind that would have sent us down to White Sands. Recall that earlier in the morning we had watched two balloons on the horizon working tremendously hard. Once we passed Cabezon Peak, the lands of carved trenches, canyons, and mesas transformed into a more open desert plain.

Here we came to the area where the balloons had been struggling. And we came to know their struggle: there was nothing here. No wind. No speed. No movement. The balloons we had been watching were searching, up and down the air column, looking for some breeze, some small draft to ride.

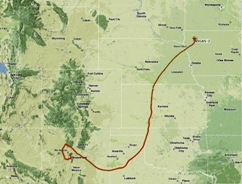

Again the names of the land help tell the story. We were at a place called Wolf Stand. It was appropriate: we stood.  Our speed was less than one mile-per-hour. Then it sank to zero. If you look at the satellite track that we broadcast out by radio beacon, there is point after point nearly on top of each other. Our gps showed us our speed: ....zero.

Our speed was less than one mile-per-hour. Then it sank to zero. If you look at the satellite track that we broadcast out by radio beacon, there is point after point nearly on top of each other. Our gps showed us our speed: ....zero.

Then we started backing up. Back towards Black Mountain. You can see the tracks doubling back on themselves, circling around like a snake biting its tail.

Then, zero again.

This was a quiet kind of battle: fighting nothingness. Our colleagues and friends had been here earlier in the day, and they were searching for winds: high, low-- anywhere to blow them out from the doldrums. We were thousands of feet in the air, unmoving.

Then, the smallest of shift. I watched the road below us. Inch by inch, we crossed it. Inch by inch, we pulled out of this dead space. I could have walked faster. I could have crawled faster. Here in the air, thousands of feet in the sky, we looked for a wind.

Thankfully, mercifully, a light draft developed which, in turn, developed into the lightest wind. This wind we would claim; with it we would begin our journey to the south-east and into the Jemez, a mountain range on the southern tip of the Rockies.

We met another kind of beauty here. Throughout the day we had been observing the splendor of remote desert. Now, we climbed into the mountains. First came forested wilderness, broken by mountain streams. We could see the shadow our balloon cast across the forest below. In the photo to the left, you can see the balloon against the Jemez forest right in the center of in the shot.

There are wonderful, unusual features in the Jemez: hot springs, sulfurous vents and a caldera - a ring of hills comprising the remains of long-extinct volcanoes. We had some concerns about tracking towards another restricted area: Los Alamos, development area for the first atomic bomb. However, this restricted area topped out at 12,000 feet. If we had to, we could climb and fly right over the top of it. However, we didn't need to- we passed about 12 miles south of that airspace.

There are wonderful, unusual features in the Jemez: hot springs, sulfurous vents and a caldera - a ring of hills comprising the remains of long-extinct volcanoes. We had some concerns about tracking towards another restricted area: Los Alamos, development area for the first atomic bomb. However, this restricted area topped out at 12,000 feet. If we had to, we could climb and fly right over the top of it. However, we didn't need to- we passed about 12 miles south of that airspace.

The heat of the day had broken, and the sun was sinking lower in the sky. Long shadows were cast into the canyons of the Jemez. As we looked out, we could see the Sandia Mountains out in front of us.

HEY. WAIT A SECOND. Did I say Sandia Mountains...in front of us? Isn't that the mountain range that borders the east side of Albuquerque, near the launch site?

HEY. WAIT A SECOND. Did I say Sandia Mountains...in front of us? Isn't that the mountain range that borders the east side of Albuquerque, near the launch site?

Um, yes. Yes they are.

That is, we were swinging back around towards our starting point. As we crossed the canyons we had the Jemez River and Jemez Mountains underneath us, and the Sandia Mountains out in front of us. We had been well on our way back home throughout the second part of this day.

Again, a little strange...in a distance race.

As the sun set in the Jemez, our chase crew-- the team of Nidia and Joe in the recovery vehicle-- hadn't left Albuquerque yet. Nidia was visiting over at the Bradley household, and our chase crew and command center crew were actually in the same place for the first day of the race! As the sun went down, we were well on our way back into Albuquerque.

As the sun set in the Jemez, our chase crew-- the team of Nidia and Joe in the recovery vehicle-- hadn't left Albuquerque yet. Nidia was visiting over at the Bradley household, and our chase crew and command center crew were actually in the same place for the first day of the race! As the sun went down, we were well on our way back into Albuquerque.

Returning home: 24-hours later

It had been a beautiful day spent aloft. Instead of shooting east out of Albuquerque, as launches from this site often do, we went west and toured some of the most beautiful scenery I have ever known.

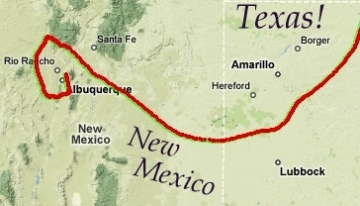

Our progress was much as we would have projected. Hysplit trajectories run before launch showed just this sort of curly-Q loopback.

After spending the day in flight, we had flown a track over the ground of about 188 miles. However, after 24-hours in flight, we could once again see our launch field! We were only 23 miles from Fiesta Park. This was supposed to be a distance race! Ok, it is as expected-- but still!

As we came out of the Jemez and the sun set, we transformed the basket. I put fresh batteries in the halogen beacons and tossed them over the side, to hang suspended in space below us. We pulled our cold weather gear in; it had spent the day hanging on the outside of the basket.

There is quite a change between the day and night on board the gas balloon. In the middle of the day, over the deeply carved lands and mesas, it had grown very hot. Now, the cold was coming.

The cold night:

With the sun set, we chose an altitude where we hoped the winds would allow us to slip between two large two mountain ranges: the Sandia Mountains to the south of us, and Santa Fe’s Sangre de Christo mountains to the north.

To fly between these two larger ranges, we would have to cross the Ortiz Mountains, at night. To help navigate the passage over the Ortiz, and between the two large mountain ranges, we started using the ground-collision avoidance system more. The device had detailed elevation and obstacle profiles pre-loaded and it would use our GPS location and altitude to warn us of impending ground strikes. Yellow and red regions on the contour terrain mapping warned us and helped us maintain the altitudes needed. Yellow meant we would be close; red meant we would hit.

Our track had us heading right towards Placer Mountain. We could expend ballast and climb above it, but we wanted to preserve this resource; also, the winds higher aloft might not have allowed us to go the way we wanted. If you look at the track, we were heading right at Placer—but we curved, sliding right around the peak, and then turned again after we had passed by. It was as if a motorcycle swerved around a ground obstacle, then continued on its path.

Our track had us heading right towards Placer Mountain. We could expend ballast and climb above it, but we wanted to preserve this resource; also, the winds higher aloft might not have allowed us to go the way we wanted. If you look at the track, we were heading right at Placer—but we curved, sliding right around the peak, and then turned again after we had passed by. It was as if a motorcycle swerved around a ground obstacle, then continued on its path.

Troy was piloting this time, and I rested some. Once we cleared the Ortiz ridges, we slipped out towards the open lands of San Miguel and Guadalupe counties. We’d been flying for over a day, but we hadn't yet touched the gas vent line; we hadn't released any of our helium out from the top of the balloon.

We traded positions and I took control of the balloon as Troy slept. I watched our elevation following the ground contours and obstacle information on the little 2x3 screen. We were in dark, open, abandoned land between Roswell and Santa Rosa. Watching the little collision-avoidance screen became entrancing. It was very cold, and even with many layers on, I was so cold. We had chemical heat packs that I burst open and tried to get to my legs. They didn’t help much. We slipped into the airspace of the Pecos North Military Operations Area, and it was really freezing. I had everything on-- face mask, hat, hood, gloves, ski pants, two jackets.

I was watching the small screen, to make sure we wouldn't hit anything coming up. Then, I looked out into the dark of the night-- and I saw dozens of TOWERS, right in our midst. My heart dropped. There were no obstacles projected in this area! The computer didn't have anything, the screen was clear! But, as I looked out of the basket into the empty night, in my sleepy and dazed state I saw dozens of lights come on around me and my brain screamed TOWERS! I thought we had moved into some radio array in the middle of the desert.

They were, actually, on the ground. What seemed like a vast array of towers was a series of ground-based lights. They were red lights spreading over the course of miles, all coming on at the same moment, then blinking out again. To this day, I still don't know exactly what they were-- part of a military or scientific installation? I'm sure it's not mysterious, but floating in the dead cold of night, silent, tired, and freezing over the Roswell desert, it gave me quite a start.

I adjusted, calmed down, and flew on. I used the radio a little, talking to Albuquerque Center to verify that the Bronco Military Operation Areas were not hot, as we were moving that way.

Perhaps around 3:00am Troy awoke, and he didn't like our track. We were going too much to the south-east. Instead he opened the vent, released that helium out into space, and dropped the balloon closer to the surface.

Troy would pilot the balloon through the dead of the night and on to dawn, taking us down to perhaps a thousand feet above the surface, and I slept.

Awake! Near Earth, and Above Texas:

Awake! Near Earth, and Above Texas:

I awoke just before the morning sun broke the horizon.

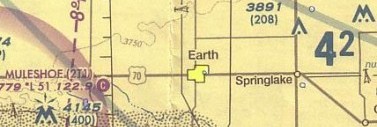

I rose from the bottom of the basket and peered out. In the night, at around 5:00am, we had crossed into Texas. We were now flying near Earth in two distinct ways:

1.) Troy had us flying low, close to the surface, to take advantage of the best track: winds out of 252, heading 072 just after dawn.

2.)We were floating near the Texas community of 'Earth'-- a town of about 293 families.

The farming methods in this part of the country involve 'pivot irrigation' where the watering equipment rotates around a central point. The resulting circular farms looked like pie charts spread out to the edge of vision, like some statistician's fever dream.

In the photo on the right, you can see Troy sitting in the basket as the sun was coming up on Day Two. It gives a good feel for the basket-- I'm standing and taking the photo. It also shows our position relative to the surface-- we were pretty low when the sun came up.

In the photo on the right, you can see Troy sitting in the basket as the sun was coming up on Day Two. It gives a good feel for the basket-- I'm standing and taking the photo. It also shows our position relative to the surface-- we were pretty low when the sun came up.

By the time we floated by the farm community in the photo to the left, the sun had been shining for some time, and it warmed our balloon. The expanding envelope caused us to start a climb, and by the time we floated past that small town, we had doubled our altitude.

Morning on a gas balloon is an interesting time. I was very grateful to be out of the cold night. I had those little chemical heat packs all over, but I had been freezing in the night.

Morning on a gas balloon is an interesting time. I was very grateful to be out of the cold night. I had those little chemical heat packs all over, but I had been freezing in the night.

However, all of that changes as the light switches and you move into day. Instead of protecting from the cold, you need to protect from the high altitude sun, and the heat. There is a real transformation in the gondola between night and day. Oh, also-- I don't think I had ever brushed my teeth on a balloon before.

Flying the Canyons:

It's like we made a wrong turn. I mean, I remember my geography, and I would SWEAR we shouldn't be flying over the Grand Canyon. I mean, that is really in the other direction.

It's like we made a wrong turn. I mean, I remember my geography, and I would SWEAR we shouldn't be flying over the Grand Canyon. I mean, that is really in the other direction.

But, there we were. I looked it up later, and Palo Duro Canyon, the area we were actually flying over, is described as "The Grand Canyon of Texas." So, I was justified in my interpretation!

It is here, in the Palo Duro State Park, that friends have flown in the "Pirates of the Canyon" balloon rally. Officially it's the Amarillo Invitational Balloon Rally, but I like the idea of sky-pirate balloonists, so I'm staying with that. Sounds steampunk. Luckily, we weren't boarded.

It is here, in the Palo Duro State Park, that friends have flown in the "Pirates of the Canyon" balloon rally. Officially it's the Amarillo Invitational Balloon Rally, but I like the idea of sky-pirate balloonists, so I'm staying with that. Sounds steampunk. Luckily, we weren't boarded.

You can see how the topography has changed. There are no more circle farms, and the earth has shades of red in it that I usually associate with New Mexico, Colorado, or Arizona. I hadn't seen this side of Texas-- and I got my undergraduate degree from The University of Texas at Austin! I was an Austenite, but I hadn't seen this part of my state.

Heat of the day, through to sunset:

We continued our track to the northeast, floating over this lake on our way to the Oklahoma panhandle. The heat picked up, and I sought cover from the sun by hiding in the bottom of the gondola and shooting photos through basket step.

Notice the bags on either side of the photo below. These are the ballast bags hanging on the outside of the basket-- and the camera lens is poking out through the step hole-- as seen on the right. This was so I could get out of the high-altitude sun for a while!

Oklahoma, and Night Three:

As we headed to the Oklahoma panhandle, we had another tremendous sunset. I was somewhat fatigued, after nearly two days in the elements. We had completely open skies-- as we had the entire flight. Our recovery crew, Nidia and Joe, were now chasing us across the states. They were there, thousands of feet below us, talking with our meteorologist by cell phone, or speaking with us over the satellite phone. They actually got a visual on us multiple times during the chase-- pretty amazing considering the 1,000+ mile trek we were undertaking.

The previous night I had really been freezing, so I had some real dread going into this, our third night. I pulled in all the cold-weather gear, and added all my protective layers in preparation for a bitter night. In some very real ways this race of ours is about endurance-- how long you can keep yourself aloft, through heat, cold, and days of exposure. In general, we were doing great. Our food supply helped-- I should eat so good on a daily basis!

The previous night I had really been freezing, so I had some real dread going into this, our third night. I pulled in all the cold-weather gear, and added all my protective layers in preparation for a bitter night. In some very real ways this race of ours is about endurance-- how long you can keep yourself aloft, through heat, cold, and days of exposure. In general, we were doing great. Our food supply helped-- I should eat so good on a daily basis!

Thankfully, this night was not nearly as cold. As we progressed out from the high-mountain deserts of New Mexico, the surface elevation bled away. So, even maintaining the same height above the ground during the night, we were much lower in terms of 'feet above sea level.'

In the photo above I am down on the floor of the basket, looking up. We have two tiny lights attached to the sun-shade on the top of the gondola, which cast a gentle glow about the basket. I heard sounds I didn't recognize, and I asked Troy if he heard them. He responds: "Oil wells." We're now flying over Oklahoma oil country. Our first night, coyotes called out to us. Tonight, the sounds of the oil wells come up to us throughout the night.

Dawn over Kansas: Throwing over our Food:

We made it through the third night, and by first light on day three we were over Kansas. Talking with our meteorologist, the best winds were pretty high. We needed to climb, a lot, to get the best winds. However, by this time we were starting to run low on ballast; we could drop our sand to climb, but then we might not have enough to make a safe landing.

Instead, we threw our food overboard.

It was sent out of the basket, careening thousands of feet down to the open Kansas plains below us. It's such a strange sport where sand becomes precious, and food expendable.

By the way, are you allowed to throw bananas out of an airplane (or a balloon, as the case may be?) Yep-- you are, as long as you take reasonable precautions to avoid injury or damage to the persons or property below. Really. See Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations, also known as Federal Aviation Regulations part 91, Section 15: Dropping Objects:

"91.15: No pilot in command of a civil aircraft may allow any object to be dropped from that aircraft in flight that creates a hazard to persons or property. However, this section does not prohibit the dropping of any object if reasonable precautions are taken to avoid injury or damage to persons or property"

Then went the veggies.

Finally went the bread.

We were in pretty remote areas-- but one has to wonder: if someone happened to experience dozens of bananas falling from the sky, just how would they explain that? I mean, how would they reconcile it in their mind? We were a tiny dot in the sky, thousands of feet overhead. It's unlikely they would see us, even searching the skies for the source of the banana rain. In Kansas, perhaps best just to chalk it up to flying monkeys.

Speeding across the Plains:

Dropping the food worked. We actually dropped more than what is pictured above, plus we released some sand ballast. With that, plus the morning sun shining on the envelope, we climbed high, into fast winds.

The balloon filled out gloriously above our heads.

Note the emergency port-- and the duct tape from three days before! Also note that you can see up into the balloon, all the way to the valve on the top of the envelope; the appendix is open, and the blue line goes up to the disk valve at the top of the balloon. The other line, which is intentionally different in color, texture, and shape, goes to the deflation port. Pull this deflation redline once, and the balloon deflates-- and there is no stopping it once it has been pulled-- it is a one-shot deal. Don't pull the wrong line while at altitude.

Our flight thus far had been in perfectly clear skies. Now, we were approaching cloud layers-- beautiful clouds. We were flying high, and would be thousands of feet above the first wave of clouds we would encounter. It would actually be an amazing tour of cloud types-- over the course of many hours we would see a wonderful variety; at one point, we would be flying right between two distinct layers-- just sailing both above and below the clouds, at the same moment.

Our flight thus far had been in perfectly clear skies. Now, we were approaching cloud layers-- beautiful clouds. We were flying high, and would be thousands of feet above the first wave of clouds we would encounter. It would actually be an amazing tour of cloud types-- over the course of many hours we would see a wonderful variety; at one point, we would be flying right between two distinct layers-- just sailing both above and below the clouds, at the same moment.

Notice the trail rope in the foreground-- this is an iconic component of gas ballooning. At landing, it is used to help arrest a sharp descent and also spin the balloon around to orient it in the right direction.

When we release this ball of rope, it trundles out below us, dragging across the earth. We can be coming down very fast, and as this rope hits the earth and starts coiling or dragging on the ground, the weight the balloon is supporting diminishes, and the rate of descent decreases so we don't slap the ground too hard.

When we release this ball of rope, it trundles out below us, dragging across the earth. We can be coming down very fast, and as this rope hits the earth and starts coiling or dragging on the ground, the weight the balloon is supporting diminishes, and the rate of descent decreases so we don't slap the ground too hard.

The trail rope also spins the balloon at landing so the so the deflation ports will be pointed 'up' and gas can be opened, releasing the lighter-than-air gas. Otherwise, if your deflation ports are pointed earthwards, the gas won't escape and you can end up dragging across the ground for far too long to be comfortable.

We were also really moving now: up to 50 miles per hour. In the span of a few minutes over the Kansas plains, we generated greater distance between ourselves and our launch site than we did in our entire the first day in flight. 50 miles per hour-- now we're in a race!

We were also really moving now: up to 50 miles per hour. In the span of a few minutes over the Kansas plains, we generated greater distance between ourselves and our launch site than we did in our entire the first day in flight. 50 miles per hour-- now we're in a race!

We were clipping across Kansas, heading practically due north. The clouds under us change regularly, giving us a tour of the beauty of the sky.

Tour du Clouds: Into Nebraska

We broke the Kansas/Nebraska state line, and entered Cornhusker country. Here we slipped between two layers of clouds, while maintaining visual reference with the ground. It was a moment of tremendous beauty.

We broke the Kansas/Nebraska state line, and entered Cornhusker country. Here we slipped between two layers of clouds, while maintaining visual reference with the ground. It was a moment of tremendous beauty.

On the left side of the photo you can see the sun guard that Garry had sewn for the system. It could be flapped down on each side to provide respite from the high-altitude sun.

One thing that is often overlooked in the photo here are the helmets. The photo is light and magical-- but that is a metal frame overhead; the basket is suspended by flexible cables. At landing,

when the basket strikes, the cables can flex, and that steel cage can come down and --- well, let's just say that the helmets aren't purely decorative.

when the basket strikes, the cables can flex, and that steel cage can come down and --- well, let's just say that the helmets aren't purely decorative.

The speed ensured a rapidly changing view unfolded below us. Counties ticked by underneath us as an infinite variety of clouds presented themselves.

Basket space was at a premium. The gondola was 3-feet by 5-feet. By myself, I'm 6" 2'. We had gear suspended over the side, and some of it hung quite far below the basket. It would be very interesting to see the side view, with camera bags and non-essential gear suspended far below the gondola level, hanging in quiet space.

Gas balloon calculations: enough to make it?

We performed careful analysis of our ballast situation. By this point, 60 hours into the flight, we had used the majority of the sand we had carried aloft.

This shot shows most of what we have left in terms of ballast: two blue bags (wet sand) two red bags (dry sand), and one black bag (10L water.) In addition, we have one bag in the hopper.

There is no ballast around the rest of the gondola--this is it.

We can drop the sand, and the water. Then.... then we'd be dropping gear to stay aloft. If we were in a remote area,  we could drop batteries-- 5 pound lead/chemical bricks; If we were coming down fast, and needed to stay aloft to stay alive, we could ballast those, and personal gear, if we needed to.

we could drop batteries-- 5 pound lead/chemical bricks; If we were coming down fast, and needed to stay aloft to stay alive, we could ballast those, and personal gear, if we needed to.

We were not at that point-- we had the bags to fly the day, and land. We were just doing the mental calculations, and arranging the basket. We sorted the gear on the aircraft counter-clockwise around the basket, in the order that they would be dropped: first sand from the hopper; then the wet sand; then the dry sand; bag of water; batteries; gear.

I honestly looked at the floor of the basket with an eye to its weight, the risk dropping it would pose, and the difficulty in replacing it. Troy eyed me warily; I don't think he liked me eyeing his perfectly good balloon basket floor as potential ballast. I had already weighed my clothing by this point, wondering if I would be able to order a new America's Challenge jacket if I had to drop mine in an emergency.

Crossing the Missouri, and into Iowa:

We approached the border between Nebraska and Iowa: the Missouri River. Right at the point of our crossing there was a coal-fired power plant, fed by black mountains of coal, spawning huge high-voltage lines. These stretched out deep into Iowa. At our altitude the plant and its powerlines posed no problem. It was an interesting sight on our gas balloon flight: the headwaters of high-voltage hummers.

We approached the border between Nebraska and Iowa: the Missouri River. Right at the point of our crossing there was a coal-fired power plant, fed by black mountains of coal, spawning huge high-voltage lines. These stretched out deep into Iowa. At our altitude the plant and its powerlines posed no problem. It was an interesting sight on our gas balloon flight: the headwaters of high-voltage hummers.

The day was growing long. Ballasting our food earlier in the day helped us climb up to the high-speed winds; however, we also had to expend primary ballast to get to the altitudes we wanted. That didn't leave us with a lot of ballast.

We consulted with our team meteorologist via satellite phone: there was weather ahead that boded poorly for gas balloons: cold, and precipitation. This leads to bad things for gas balloons: something heavy accumulating on top of the balloon, adding weight, and pushing one to earth.  This would be after three nights already spent aloft-- when our ballast was already low. In addition, our flood light was malfunctioning. If we had to do a night landing, we'd be blind to what was below us. Trees? Powerlines? Open fields? Or is that water?

This would be after three nights already spent aloft-- when our ballast was already low. In addition, our flood light was malfunctioning. If we had to do a night landing, we'd be blind to what was below us. Trees? Powerlines? Open fields? Or is that water?

No. Frozen rain, and a night landing with no spotlight was not for us. We had a safe amount of ballast to land with; there would be little likelihood of surviving the night, if we were to attempt it. (Some of the other balloons did try to run through the night; none of them made it to the morning sun; all landed in the dark.)

The sun sank low, Iowa corn country swept beneath us.

Bringing it in; Setting the Record; Coming to Earth:

The sun descended towards the horizon and the balloon slowly cooled, which set us into a gentle descent. We approached the third night we had seen since launching, way back in Albuquerque. However, this night we wouldn't counteract the evening's descent by releasing ballast. We would let ourselves come back to earth. I spoke to the command center in Albuquerque, letting them know we intended to return to terra firma.

The sun descended towards the horizon and the balloon slowly cooled, which set us into a gentle descent. We approached the third night we had seen since launching, way back in Albuquerque. However, this night we wouldn't counteract the evening's descent by releasing ballast. We would let ourselves come back to earth. I spoke to the command center in Albuquerque, letting them know we intended to return to terra firma.

Allowing the balloon to descend, without any counteracting ballast release, committed us to landing. Winds on the surface were unfavorable: they would blow us west-- and the hard-earned miles we had added between us and our launch site would slip away. Every minute we stayed aloft at low altitudes would decrease our Great Circle distance.

We methodically prepared the basket, making sure absolutely everything was clipped in, and trying to pack soft gear around hard gear. If we were going to be bashed by a 5-pound lead brick battery during a rough landing, better if that battery was at least wrapped up in a soft sleeping bag. (Though, it does seem that we had more hard things to worry about than we had soft things to protect us.)

Clipping in the gear was extremely important: if you strike the earth, have the basket tip, and then lose gear-- you suddenly lose weight, and you can end up ascending again, only to slap down again as you vent the gas. Best to have everything clipped in.

The flight had been fantastic. One America's Challenge balloon was still aloft: Delta Goodie, piloted by Mark Sullivan and Cheri White. We didn't know if Mark and Cheri would progress into the night, or if they would land before nightfall. Our decision to land would be independent of what Mark and Cheri would do; we knew our ballast situation, and we had good information about the weather in front of us. When we chose to hold on to our remaining ballast as the sun set low, instead of dropping it to stay aloft in the favorable winds, we were committed to landing this sunset.

We just had to bring it in and touch the earth. Without incident.

LANDING:

As we came low, our track changed and we headed west. This was as expected, but still it was difficult to see our miles-since-launch decreasing! Our descent from altitude had been gentle, requiring very little ballast to keep a smooth rate of descent going. Landing a gas balloon is a little different than hot-air. With the trail rope acting to slow descent in the last 50 feet, you can come in at a much steeper approach and still be ok at landing. A little disconcerting to watch, if you're used to hot-air. Talk about ground-rush.

Things became very serious. We were perhaps a few hundred feet off the ground, and we saw our field ahead of us: the crop had been harvested, and it looked fine, aside from the giant bales scattered here and there. We would cross a dirt road right before the field, and we had to assume that there would be powerlines along that road. So we couldn't deploy the trail rope until crossing that dirt road.

We were moving about 20 miles per hour. Troy had the valve line (blue) and vent line (red) close at hand. I would deploy the trail rope, make sure that it unrolled all the way, then grab ballast.

We were moving about 20 miles per hour. Troy had the valve line (blue) and vent line (red) close at hand. I would deploy the trail rope, make sure that it unrolled all the way, then grab ballast.

I'm looking out the back of the basket with the quick-pin for the trail rope in my hand. I'm watching closely for lines over the road. It's here- road underneath us. "I'm pulling the pin! The trail rope is dropping! It has uncoiled fully-- successfully uncoiled!"

Troy is on the valve line as I grab a bag of ballast. Troy instructs: "Drop half bag!" I do, pouring sand over the side as I read out our descent rate. He's watching the earth, hands on the lines. I'm reading out the rate of descent from the flight computer.

Troy calls: "WHOLE BAG!"

I drop the whole bag, canvas sack and all, over the side and quickly grab another bag. We were rapidly approaching one of the giant bales dotted across the field. They looked a lot smaller from aloft--- as we approached one, it suddenly looked a lot bigger. It wouldn't be the worst thing to smack into at 20mph, but it wouldn't be good either.

The bag I dropped allowed us to clear the giant bale, and Troy was again working the valve. The ground approached rapidly. Knees bent! LOW in the basket! STAY IN THE BALLOON!

We hit.

BANG! Earth-- and we're dragging! The basket is laying horizontal along the ground. As we tipped, Troy ripped the redline, pulling the release and allowing the deflation port to open. Helium began escaping to space-- we were moving at 20mph when we hit. The trail rope has done it's job, orienting us correctly. The redline was pulled, which is a one-shot deal.

BANG! Earth-- and we're dragging! The basket is laying horizontal along the ground. As we tipped, Troy ripped the redline, pulling the release and allowing the deflation port to open. Helium began escaping to space-- we were moving at 20mph when we hit. The trail rope has done it's job, orienting us correctly. The redline was pulled, which is a one-shot deal.

We're dragging still, the balloon is rapidly deflating.

We come to a stop!

High Fives!

Call the command center, let them know we're home.

The Victors, The Ceremony, The Awards!

In our great 2008 America's Challenge race, we all returned safely; each balloon and all pilots safely touched down again. A great year!

In our great 2008 America's Challenge race, we all returned safely; each balloon and all pilots safely touched down again. A great year!

Troy and I flew 68 hours, 46 minutes. In doing so, we captured the America's Challenge duration record. (Mark and Cheri landed 7 minutes after us, but since we launched 16 minutes before them, we had been aloft just a little bit longer. Small margin on a 68-hour flight!)

Phil MacNutt and Phil Bryant flew a great-circle distance of 672 miles, and claimed 3rd place. Troy and I flew 1,214 miles-- which yielded a great-circle distance of 790 miles. I was extremely proud to take 2nd place.

Mark Sullivan and Cheri White flew a great-circle of distance of 881 miles, making the pair the undisputed champions for 2008!

Congratulations to Mark, Cheri, and all the gas balloon pilots that flew the early October skies!

After we landed, our chase crew was with us within 30 minutes-- a remarkable achievement in a gas chase! After racing for days to get away from Albuquerque, we now embarked on a terrestrial race to get back again-- to be there in time for the treasured gas balloon awards ceremony.

We made it; we arrived in Albuquerque Saturday morning, in time to rest and attend the gala awards banquet Saturday evening. While I was perhaps a little bleary eyed, the collected group was resplendent; it was an honor to be there, to be in the company of these great balloon pilots, and to have flown America's Challenge 2008.

With Great Appreciation:

My heartfelt thanks go to:

- The Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta

- Pat Brake, Event Director for the 2008 America's Challenge Gas Balloon Race

- Garry Haruska, Balloonmeister, for turning a bag of material into the proud aircraft we would call home

- Joe Bosco, for chasing our balloon across the continent, and recovering us safely

- Scott Risch, for his meteorological expertise and dedication-- guiding us --day in, day out, and in the dead of night

- Tim Baggett, for collecting, transforming, and presenting the gps data that has allowed me to re-create, and re-live, this flight

- Keith Sproul, for encouragement during my gas training, and for helping us set the balloon aloft

- David Bair, for help before the race, through the briefings, and in the Command Center during the flight

- Martha and Ruben Ruiz, Keith Yohai, and Mario Cisneros for coming to see us off, and cheering us on in flight

- Bob Berben, event winner and distance record holder, along with Nicolas Berben and the Berben family, for hospitality in Belgium, gas balloon training in Germany, and for cheering that could be heard around the world

- Willie Eimers, the most experienced gas balloonist in history, for hosting us at the Gladbeck Gasballon Startzplätz-- better know as the Willie Eimers balloon port

- Peter Van Overwalle, for a goofy Pink-Elephant balloon, and for graciously chasing us across the German countryside as I pursued my gas rating

- Walter Snyder, for being gracious volunteer crew in Albuquerque

- Mark Caviezel, for ongoing ballooning camaraderie, and always being excited about flying gas

- My colleagues, executives, and boss at Accenture, for tracking me in flight, cheering me on, and manning the Accenture ship while I floated in the sky

- Fellow gas balloonists, racing across the sky, for camaraderie, excitement, and one hell of a race

- Beth Wright-Smith, for building a foundation in safety during my training at Airborne Heat

- Everyone who manned the gas balloon command center, ensuring a lifeline to the world

- Balloon Team Fly One for help on the field, preparing our balloon to go aloft

- North Carolina Balloonists Ken Draughn, Tom Tomassetti, and Brian Hoyle for tutelage and patience in helping a new balloonist

- Whit Landvater, for building ClusterBalloon.com, and for helping with this page

- Andy Baird and Rick Jones, BFA Presidents, for encouragement and guidance in entering the world of ballooning

- BallonSport Magazin, and Photographer Ben Blaess, for permission to use BallonSport cover photo

- Cindy Petrehn: for sharing her wonderful photographs, from the launch through to the awards ceremony

- Tami Bradley, gas balloonist and former America's Challenge winner, for manning the personal command center, for gracious hospitality, and for allowing us to steal her husband aloft

- Special thank you to world-class gas balloonist, mentor, and friend Troy Bradley

- Endless thank you to Nidia Ruiz Ramirez

Additional Accounts: